How to Talk to an Upset Student

A powerful listening skill that helps you get to the heart of the matter.

Ella shuffles into my studio, half-size guitar dangling in one hand, and Mattie, her doll, in the other. Just six years old, Ella is one of my youngest students. She’s usually bubbly, and last week she left excited to work on the two new songs she was preparing for the fall Jam (the name for my student concerts).

But today she’s acting like Halloween got cancelled.

“I don’t want to play in the Jam,” she pouts, slouching into her chair. “It’s dumb.”

***Cue Record Scratch Sound***

If you were me, what’s the next thing you’d say to this student? Would you ask her why? Reassure her? Remind her of the educational benefits of performing music? Tell her how fun it’s going to be?

What if I told you that it’s best to respond in another way entirely?

The skill I want to teach you is called empathic listening. I learned it almost two decades ago, and it has vastly improved my relationships. It’s helped me grow closer to difficult family members. It’s helped me earn the trust of my friends, who now come to me for support and advice when they’re struggling. It’s kept my marriage strong through the daily stresses of raising children. And if I had to list the reasons why I have low attrition--most of my private music students have been with me over six years--this skill would be near the top.

CAUTION

If you’ve been trained in listening skills, you’ve probably learned “active” or “reflective” listening, which basically involves mimicking what someone else says. This kind of listening can often feel fake and manipulative.

Why? Because when people share something emotional, they desperately want to be understood--not only intellectually, but also how they feel. And reflective listening ignores a person’s emotion.

Why Does Empathic Listening Work?

Empathic listening means listening with an intent to deeply understand someone, both on an intellectual and emotional level. It’s exactly what our students, or anyone, craves when they’re upset. Stephen Covey, who teaches empathic listening in his book The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People, compares this need to our physical need for oxygen:

If all the air were suddenly sucked out of the room you're in right now, what would happen to your interest in this book? You wouldn't care about the book; you wouldn't care about anything except getting air. Survival would be your only motivation….

...Next to physical survival, the greatest need of a human being is psychological survival--to be understood, to be affirmed, to be validated, to be appreciated. When you listen with empathy to another person, you give that person psychological air. And after that vital need is met, you can then focus on influencing or problem solving.

If you look back on lessons with students who were in emotional turmoil, do you remember how hard--often impossible--it was to teach them anything? At least until they felt understood? Those students were drowning in their emotions, and could care less about the 16th note pickup you were explaining. Until they feel understood, they can't learn.

The Challenge of Empathic Listening

The steps of empathic listening are easy to follow with a little practice. But the mindset they require is difficult.

You must truly be listening with the intent to understand.

You must temporarily put aside your teacher’s urge to instruct, to say something like: “Once you’re able to play your song better, you’ll feel more comfortable.” You must also be patient, resisting the urge to extract information with probing questions: “Are you upset because you’re nervous about being on stage?” You have to rein in all the well-meaning but unhelpful impulses we have to compare our students’ struggles to our own: “I used to be scared of performing when I was a kid.” You should even resist the urge to agree or disagree with your student.

All these responses are unhelpful because they get in the way of the students telling you what’s going on. And until you truly know why they’re upset, any advice you give them will be unwelcome--they want to be understood, not informed--and probably not address the problem anyway. So often we assume we know what people need without understanding them. It’s like we’re offering our extra pair of glasses to someone else: “These glasses help me see so much better. They’re just what you need.” Without first diagnosing the student’s problem, your prescription’s just going to give them blurry vision and headaches.

The 4 Steps of Empathic Listening

Follow these simple steps whenever someone’s getting emotional when they’re talking to you. Here’s how it works:

- Listen to the person, noticing their emotion

- Rephrase both intellectual content and their emotion

- Wait attentively

- Repeat until the person isn’t emotional any more or asks a question.

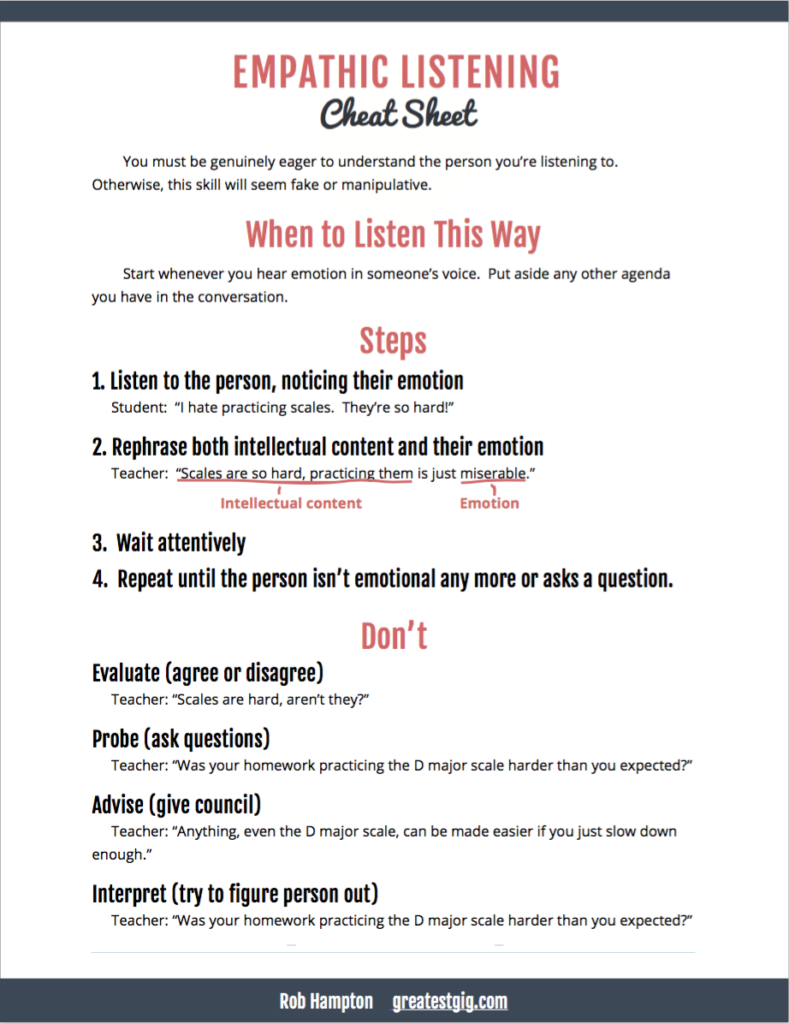

Want to use this skill with your students? Get my Empathic Listening Cheat Sheet, print it, and refer to it in between lessons until you've internalized it.

Ella's Problem

When Ella tells me that she doesn't want to perform in the Jam, and that it's “dumb,” thoughts and feelings bubble up in me. I suspect she's scared, but I'm also frustrated and confused because our last lesson had seemed to go so well. But before I start asking her probing questions or trying to reassure her (it's still my first impulse), my little “Emotion Sensor”--a kind of warning light in my mind that reminds me to listen empathically when people are emotional--lights up.

I take a moment to let Ella’s emotion resonate with me, and then say, in a quiet voice, “The Jam’s a waste of time--you don’t want to do it.” I reflected both the intellectual content--not performing in the Jam, and the emotion--It's a waste of time.

“Yeah,” she says. Silence. “Why can’t I do just one song like Mark?” Mark, her older brother, tends to learn songs one at a time, while Ella, like most of my young students, seems to prefer the variety of having lots of songs to work on simultaneously.

“You just want to do one song like your brother,” I say. Notice I don't answer her question. She's still emotional, so I'm still just listening.

“Yeah, ‘cause Mark gets to just do one song and he gets really good at it,” she says, her face crumpling, “and I have to do all these songs and I can’t remember them!” She starts sobbing in her hands.

Now we were getting to the heart of the matter. After another couple minutes of listening, I discovered Ella had gone home after our last lesson, and forgotten how to play the two new songs I had given her. Anxious thoughts consumed her. She’d imagined being on stage at the upcoming Jam, still underprepared and overwhelmed. And she started feeling resentment toward her brother, who seemed to be getting a lighter workload.

Here I’d been piling on new material, thinking I was doing her a favor by providing her more variety.

Once Ella felt understood, the tears dried and we came up with a plan to only work on one song at a time. By the time the Jam arrived, she had still learned two songs as we had originally planned, but had worked on them one-by-one, as she preferred.

Her performances at the Jam were great, and ever since that day, it’s felt like Ella and I see eye-to-eye. She takes more risks, and voices her preferences confidently. She feels more understood by me, and trusts me. She’s ready to learn.

BLOG POST DOWNLOAD:

Empathic Listening Cheat Sheet

Don't forget what you've learned! Print this one-page cheat sheet and refer to it in between lessons.

Want to hear this skill being used? My buddy Jordan and I demonstrate it in my Friday Live Show on empathic listening.